Friday, November 24, 2006

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

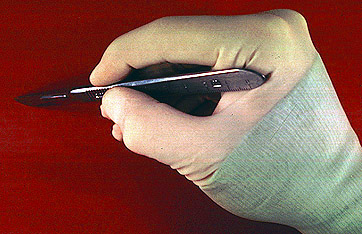

Fast Fiction: Cut to the Future.

It, the blood, pools at his feet, his thirteen year old feet. Life sucked from flesh, to give life to flesh. White tiles reflect his face as he bends to the mop and paints the red in swathes across the floor.

Sounds of suction and flash of steel gone now for an hour, Paul is left alone in the vaulted room, the room that ascends into darkness beyond the halogen lights suspended above a steel operating table.

The arteries and veins that make up the anesthiologists equipment, coiled like intestines in the corner of the room. "He makes me do this, I make myself do this." Paul thinks

Day after day, week after week Paul witness's the charnel house that is modern medicine. He witness's brothers, husbands, wives, mothers, fathers, friends and cousins being transformed from breathing personalities into examples of the surgeons art.

Into examples of his fathers art.

Bisected with incisions sealed with stitches, the doll makers art.

Sometimes he is let watch.

"Sometimes he makes, no that’s wrong, sometimes he lets me watch. This man hardly seems like my father, tall and obscured in resplendent white, that gradually turns to red as the grand guignol humour grows with every incision, with every clamp, with every suture. But every day he becomes less my father, and more that hunched creature of my dreams with its small silver box of surgical tools."

This is how the boy spends his Summer holidays.

The precious time when others, beyond those hospital walls date girls, get drunk, party, and explore the terrain of LetterKenny, its parks, alleyways and coast. The endless variation of teenage years, of teenage exploration. As these teens explore their world, and their identities, Paul sees only red.

As white clouds in time lapse photography speed overhead to the accompaniment of wind chimes, Paul in his fathers surgical dungeon fills white bins full of medical waste, of rotten sections of bowel, of flailed kidneys, of gangrened and necrotic limbs.

The only girls he gets to see are those that lie pale and silent, fluorescent in the glow of the halogen. From a distance, from the corner of his small world, hidden in the shadows, he watches their pale breasts rise and fall, and from below, he hears, but does not see the work of the surgeons knife as it pushes into virgin flesh, tearing through the derma and below, through the organs. All the time, the breasts rising and falling in time with his own breathing, in time with his hand, friction against his crotch. No one else in the theatre sees, this he knows, all eyes are on the patient, and the incessantly beeping cardiographs that tell them they are still in no danger of a malpractice suit.

At home there is not even the noise of the ventilator, nor the light of the halogen lamps. At home there is not even books.

There is only Father, sitting in silence at the head of the table, he glances up, and begins to whisper grace. Then leaning over his paper and chewing each slice of rare meat forty times before swallowing. Paul counts each chew in his head, one, two, three...and on and on. The boy has long finished his meal by the time his father has swallowed the last piece of masticated flesh, but he is not permitted to leave the table without fathers permission. He lowers his head and waits for the baritone of Father to give the permission he needs so every night.

And so it goes.

But where does Paul go? As bones grow, sinews strengthen and the boy becomes a man, he goes forward in time, toward the end of his education, and further into all our nightmares.

The Doctor will see you now.Peace and Hope